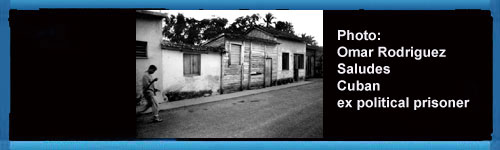

For an Exiled Cuban Photographer, Freedom Was in Color. By David Gonzalez.

Freedom was in color. That was the indelible memory that Omar Rodríguez Saludes remembered the day he boarded an Iberia flight to Spain from Havana in 2010. Until then, his world was sketched in drab shades of gray, green and white. Those were the colors of his imprisonment: gray for his rags, white for the walls and green for the guards.

“To see any other color was rare,” Mr. Rodríguez Saludes said. “But in that plane, I saw colors. Everyone was dressed regularly. I saw colors I had not seen in a long time.”

Seven years, to be exact. Journalism was the reason for his imprisonment. Specifically, everyday shots of Havana life, far from the gleaming tourist hotels and beaches. His world showed a crumbling city with haggard faces, presided over, Oz-like, by billboards with revolutionary slogans.

He had been among some 20 independent journalists who were rounded up by the Cuban government during a sweep of 75 dissidents in March 2003, and given lengthy sentences after quick trials. They were said to be traitors and mercenaries in the service of the United States government, even though international human rights and journalists groups defended them as prisoners of conscience.

Mr. Rodríguez Saludes was a self-taught photographer who was considered among the best of the island’s up-and-coming independent journalists. It was not an easy life, whether dealing with daily harassment and short-term jail stays, or regularly having his camera and recorder confiscated. In a profile I wrote on him in 2002, he called himself “a blind photographer,” since he saw only his negatives, never the prints that were published in a Miami-based Cuban news service, Nueva Prensa Cubana.

Soon after the article ran, a friend of his in Miami called to thank me. The article, he said, would give his friend a higher profile and, perhaps, a measure of protection.

That’s relative. Mr. Rodríguez Saludes was sentenced to 27 years, the longest of any independent journalist. He got off easy: prosecutors had asked for a life term. Mr. Rodríguez Saludes served seven years before being sent into exile to Spain with his family, where he now lives (though has been unable to find work).

“You have to have courage to do this work,” said Carlos Lauria of the Committee to Protect Journalists. “Omar’s case was one of the longest sentences they gave to anyone. It is a faithful reflection of an arbitrary system that has a totally obsolete legal framework. It is totally repressive and looking to stifle any kind of expression.”

Mr. Rodríguez Saludes did not start out to be a journalist or dissident. He had been working at a shipyard, where he saw the differences between how the company — the Cuban government — treated those who worked inside the office and those who worked fixing boats. He called it slavery. The government thought otherwise. In 1992, he lost his job.

He had become used to walking around Havana taking pictures, a hobby he had picked up from his mother, who took family photos with an old box camera. In his early 20s, he had been using a Soviet-made camera to chronicle his walks about town. His archive grew; his work prospects did not.

In 1995, Raúl Rivero, the dean of Cuba’s independent journalists, invited him to become part of the island’s growing movement. He quickly took to it.

“I was already in the streets with my camera in hand,” he said. “It was my custom, almost a vice. Even on family walks I had my camera. It was daily work that gave me a social and photographic vision. I saw things others did not. I focused on the details.”

The more he shot, the more he looked to contrast the reality on the sidewalk with the billboards and official pronouncements. Getting around on a bike, he scooted about Havana looking for those contrasts.

“I had to be fast,” he said. “This was before digital. Back then, the frame had to be right. I had one or two shots to get it. I tried to show the reality as it is. I wanted to speak loudly about the reality facing Cubans, and to show it was not he paradise the government presents. They try to say it is clean and stable. But reality is far from that.”

Though he had often been detained — losing his cameras to an agent of state security who hung one in his office like a trophy — things took a serious turn for the worse in March 2003, the time that came to be known as Cuba’s Black Spring. He said that agents showed up at his home and searched it, taking books, cameras and even medicine sent by his mother from Miami.

One particular prize was the 2002 New York Times article.

“When they found it in a drawer, one of the agents said, ‘Look at this!’ when I turned around, I saw it was the New York Times article,” he said. “They used it as evidence against me in their prosecution, as if it had been a nuclear weapon.”

While in custody, he was repeatedly questioned.

“They started to talk to me about the news, who spoke to me, how did I get the news, what did I do with it,” he said. “From the beginning, the only words I said was ‘No, I will not respond.’ They knew the answers already. That was public. The problem was I did not want to cooperate. You can’t cooperate with them.”

His trial lasted hours. His sentence, years. He spent his first nine months in an isolation cell, he said, and was later sent to different prisons, often making it hard for his wife and children to visit. During those years, he managed to keep a diary.

He was freed in July 2010, thanks to the intercession of the Cardinal Archbishop of Havana and the Spanish government. The offer was hardly ideal: he would have to go into exile in Spain, whose government was willing to offer resettlement assistance (which has recently run out for those exiles still there).

The conditions placed on many of the freed journalists — namely, exile — have been denounced by press freedom and human rights groups. Mr. Lauria said it was important to note that many of the former independent journalists had not been writing direct criticisms of the government or its leaders.

“It’s important to note that may of those who were jailed had once embraced Socialist ideas,” Mr. Lauria said. “But the moment they expressed themselves, they were seen not just as the opposition, but acting against the interests of the state. For something that in any normal country is not considered an aberration, but part of the game of democracy.”

Many of the former journalists have left Spain after finding it hard to find work. Mr. Rodríguez Saludes himself is unemployed despite having taken courses in three different trades. He recently decided to move to the United States, where he hopes to finish writing his prison diary.

He says he regrets nothing.

No longer a blind photographer, the only pictures he takes are with his cellphone — though they are in color, just like inside the plane that took him from Havana.

“When I walked up the steps with my family, I did not look back,” he said. “I knew they were looking at me. I knew there was hate.

“But when I got to the top of the stairs, something happened. The flight crew was there and the captain extended his hand to me. ‘Welcome to Spain, liberty and democracy.’ Then, he hugged me and my family.”

______________